Michael Stanwick

The story of the related companies of the Mah-Jongg/Mah-Jong Company of China, Shanghai, the Mah-Jongg Sales Company of San Francisco, the Mah-Jongg Sales Company of America, San Francisco and the Continental Mah-Jongg Sales Company, Amsterdam, involves seven people—Albert R. Hager and Emily Hager; Joseph P. Babcock and Norma Babcock; Anton N. Lethin and Helen Van Housen-Lethin and W. A. Hammond. It was their travels and occupations in one way or another that fortuitously brought them together and eventually led, via the aforementioned Companies, to a version of a popular Chinese game exploding onto the Western social scene – particularly the United States – in the early 1920s. The popular Chinese game was called in the local Shanghainese pronunciation 麻雀 mo ziang and in Mandarin as má jiàng which eventually was written as 麻將. In the West, the variant of the game of interest here was called Mah Jongg.

Various sources have been used to piece together the dates and locations of the events that eventually brought about the introduction of Mah Jongg to popular attention in the West.

First, in relation to the Babcock’s, are passport applications, consular applications and certificates, marriage certificates, ship passenger lists and census records. In addition is a 1923 description by Joseph Park Babcock of his encounter of the game in China and how he came to develop for Western players the tile set, the game-play and the name for his version of the Chinese game.

Second, is a 1924 testimony by Norma Babcock, relating her perspective of events that led her husband to China and to their encounters of the various Chinese versions of the game and how the game of Mah Jongg was introduced to the United States.

Third, is the testimony contained in a letter, dated Shanghai, February 18, 1923, that Anton Lethin wrote to his elder sister. This testimony describes the chance meeting the Lethins had with the Babcocks in the United States and the Lethins’ chance experience of the game in China. It also describes the formation of the Mah-Jongg Company of China and the movements of Albert Hager. The letter also provides a description of the tile set manufacturing process. In addition to his testimony we have that of his granddaughter (Lisa Lethin), which also provides valuable additional evidence.

The fourth line of evidence is drawn from various biographical dictionary sources collated by my colleague Thierry Depaulis of the International Playing Card Society. These relate to Albert Hager and Anton Lethin and give a detailed account of their time in the Philippines and China.

Fifth, are patent and trademark applications filed by Joseph Babcock and Albert Hager, that contain information about dates, companies and games’ apparatus.

Finally, are two useful resources. The first is ‘Foster on Mah Jong Mah Cheuk Ma Chang Pung Chow’ by R. F. Foster, 1924. However, information from this book must be used with caution, for there are no references of primary sources. The second is the paper ‘The Game of One Hundred Intelligences”: Mahjong, Materials, and the ‘Marketing of the Asian Exotic in the 1920s’ by Mary C. Greenfield. Although the character portrait painted of Babcock in the paper is at odds with what we know of Babcock from the relevant evidence, this paper does contain useful evidence-based data derived from sources referenced in the footnotes.

In order to determine if the information taken from second and third hand accounts or testimonies is reliable, comparisons were made with the first hand sources listed above to check for consistency. Conclusions drawn from these comparisons are flagged by caveats to show that they are considered tentative statements and should be treated as such.

All sources are referenced as Footnotes at the end of the relevant sections. Passport Application dates are taken from the date of the Oath of Allegiance on each application. Where these are not available, the Application order is taken from the Application number stamped at the top right of each Application page.

Albert Ralph Hager (1874-1952) achieved a Bachelor of Science degree in 1897. On December 21, 1904 he married Emily Read, a teacher of Salt Lake City.

In 1901 he was part of a group of teachers sent by the United States government to the Philippines on the USS Thomas. These teachers –called Thomasites – set up a new public school system and used English as a means of instruction for training Filipino teachers. From 1901-1903 Hager was an instructor in Physics at the Philippine Normal School in Manila, a post he occupied until he became Chief of the Education Department (based at the Philippine Exposition Building in Manila) of the Philippine Exposition at the St Louis Exposition from 1903-19041.

He was a member of the Clarke & Co., Technical Supply Company of China, Japan and the Philippines, with residences in Manila and Shanghai from 1905 – 1906 1, 2, and then he became General Agent for the Manila-based Asian branch of the International Correspondence Schools for China(Shanghai), Japan(Tokyo), Korea and the Philippines(Manila) from 1907 until at least 1925. This required him to travel between, and reside in, Manila, Shanghai and Tokyo 3, 4. In 1921 he started the Business Equipment Corporation, Shanghai, and then in early 1922 he became co-partner in the Mah-Jongg Company of China. According to Anton Lethin in a letter to his sister Agnes dated Shanghai, February 18, 19235.

We organised the Mah-Jongg company about a year ago forming a partnership consisting of Mr Hager, Joe Babcock, the chap that wrote the “Little Red Book of Rules” and myself [thus “about a year ago” from February 8, 1923, would place the company’s formation around late January-early February 1922].

Who Was Who in America, 1974. Published by Marquis Who’s Who in 14 chronological volumes.

Wisconsin Alumni Magazine, Loeb, Max (ed.) Volume 7, October 1905 – July 1906. Published at Madison by the Wisconsin Alumni Association as the Wisconsin Alumni Magazine from 1899 to 1935 (volumes 1-37).

The Phi Gamma Delta, Volume 34, 1911-1912. P.644.

The Educational Directory and Yearbook of China, 1918. P46. Taipei : Ch’eng Wen Publishing Company, 1973.

Anton N. Lethin. Letter to his sister, Agnes, Shanghai, February 18, 1923.

Joseph Park Babcock (1893-1949) was born in Lafayette, Indiana. In 1912 he graduated from Purdue University with a Bachelor of Science degree in Civil Engineering and resided in Lafayette with an occupation as a clerk6. He entered the Standard Oil class for foreign service7 and on July 16, 1913 he left the United States for China8.

Analyses of two of Joseph Babcock’s sea bound trips between the USA and China (USA to Shanghai (27 days)9 and Shanghai to San Francisco (25 days)10) reveals he very likely arrived in Shanghai, some time in mid August 1913, where he stayed for five months – that is, until at least the end of December 191311.

After his 5 month stay in Shanghai he arrived in Tientsin [Tianjin], Shandong Province in North China, on January 6, 1914 and was listed as “temporarily sojourning” and “residing for the purpose of business” on behalf of the Standard Oil Company, Tianjin12,13. Since he was given the post as Manager of the Standard Oil Company’s Peking [Beijing] office14 within 6 months of his arrival in China and given he most probably arrived in China sometime in mid August 1913, then within six months from that date would mean he was given the post some time before February 1914. This may account for his temporary presence in Tientsin [Tianjin] – as an intermediate stop-over for Peking.

Just under six months later, on June 25, 1914, he arrived in Peking [Beijing] where he took up residence until 191615 for the purpose of trade (as a two-year posting as Manager of the Peking Office of the Standard Oil Company of New York)16.

In or before October 1916 he left Hong Kong with Norma Nethol Noble (who he had met sometime after her arrival in China in November 1915) aboard the RMS Empress of Asia bound for Yokohama, Japan17. They arrived in Kobe where they were married, on October 5, 191618. Rejoining the RMS Empress of Asia they set sail for Victoria, Canada, arriving on October 22, 191619. They subsequently made their way to the United States for the purpose of the introduction of Norma Babcock to Joseph Babcock’s parents in Lafayette, Indiana20.

On January 17, 191721,22 they set sail on the Siberia Maru23 for Shanghai, China, arriving on February 13, 191724 and immediately travelled to Harbin, Heilongjiang province in North East China, arriving there 6 days later on February 19, 1917. They resided in Harbin until probably September of that year for the purpose of Joseph Babcock’s occupation as Manager on behalf of the Standard Oil Company of New York, based at 18 Diagonalnaya, Harbin25.

After Harbin they travelled to Soochow [Suzhou], Jiangsu province, Central China, arriving in September 1917 and where they resided for two years and seven months in Soochow [Suzhou] for the purpose of Joseph Babcock’s position of Salesman on behalf of the Standard Oil Company26.

On March 28, 1920 the Babcocks departed Shanghai and set sail aboard the S.S. Equador for San Francisco where they arrived on April 22, 192027 taking up residence on the island of Catalina28.

On July 29, 1920 the Babcocks departed San Francisco and arrived at Tsinan [Jinan], Shandong province in North China on August 19, 1920,29,30 where Joseph Babcock was the Business Representative on behalf of the Standard Oil Company of New York31.

They resided in Tsinan [Jinan] for three years after which time they travelled to Shanghai, and on the September 19, 1923 set sail aboard the S.S. President Lincoln, arriving at San Francisco on October 9, 192332 where Joseph Babcock gave his occupation as “marketer”33.

During their time in the United States Norma Babcock visited the island of Catalina on Sunday, April 13, 192434 and gave an interview for the island newspaper, The Catalina Islander.

Nine months later Joseph and Norma Babcock were booked for a return trip to China from Seattle aboard the S.S. President Grant July 31, 192435.

USA July 16, 1913 to Shanghai Aug. 1913(5 months sojourn.)

Shanghai Dec. 1913 to Tianjin Jan. 6, 1914(~ 6 months sojourn.)

Tianjin June 1914 to Peking[Beijing]. June 25, 1914(3 yrs 3 months residence.)

Peking[Beijing] 1916 to Hong Kong 1916.

Hong Kong 1916 to Yokohama(Japan). 1916.

Yokohama 1916 to Kobe(Japan) Oct. 5, 1916.

Kobe 1916 to Yokohama(Japan) 1916.

Yokohama 1916 to Victoria (Canada) Oct. 22, 1916.

Victoria 1916 to Lafayette(USA) to 1916?(2 months? sojourn.)

Lafayette 1917? to San Francisco. 1917.

San Francisco Jan. 17, 1917 to Shanghai Feb. 13, 1917.

Shanghai Feb. 1917 to Harbin Feb. 19, 1917(~ 7 months residence.)

Harbin 1917 to Suzhou Sept. 1917(~2 yrs 6 months residence.)

Suzhou March? 1920 to San Francisco Apr. 22, 1920.

San Francisco July 29, 1920 to Jinan August 19, 1920(~2 yrs 11 months residence).

Jinan 1923 to Shanghai 1923.

Shanghai Sept. 19, 1923 to San Francisco Oct. 9, 1923.

Seattle July 31, 1924 to China.

Passport Application February 7,1914. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 202; Volume #: Roll 0202 – Certificates: 21452-22300, 22 Jan 1914-11 Feb 1914.

The Catalina Islander, April 16, 1924. Page 2, cont., page 10. The Catalina Archive, http://cat.stparchive.com/1924/April%2016/

Department Passport Application April 22, 1918. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 757; Volume #: Roll 0757 – Certificates: 77750-77999, 26 Apr 1919-28 Apr 1919.

See footnote 7. Both departure and arrival dates are given in this application.

S.S. Equador Passenger List, Shanghai – San Francisco. Ancestry.com. California, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008. Original data: Selected Passenger and Crew Lists and Manifests. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Application for Registration – Native Citizen. March 2, 1917. Roll #: 32734_1220706418_0257. Original data: Department of State, Division of Passport Control Consular Registration Applications. U.S., Consular Registration Applications, 1916-1925.

Passport Application, January 12, 1914. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 202; Volume #: Roll 0202 – Certificates: 21452-22300, 22 Jan 1914-11 Feb 1914. Source Information Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007.

Certificate of Registration of American Citizen, February 17, 1914. Consular Registration Certificates, compiled 1907–1918. ARC ID: 1244186. General Records of the Department of State, 1763–2002, Record Group 59. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Ancestry.com. U.S., Consular Registration Certificates, 1907 – 1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.

See footnote 7.

See footnote 11.

Certificate of Reregistration of American Citizen. Ancestry.com. U.S., Consular Registration Certificates, 1907 – 1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013. Original data: Consular Registration Certificates, compiled 1907–1918. ARC ID: 1244186. General Records of the Department of State, 1763–2002, Record Group 59. National Archives at Washington, D.C.

(a) R.M.S Empress of Asia, passenger List. Hong Kong – Yokohama. Ancestry.com. Canadian Passenger Lists, 1865-1935 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists, 1865–1935. Microfilm Publications T-479 to T-520, T-4689 to T-4874, T-14700 to T-14939, C-4511 to C-4542. Library and Archives Canada, n.d. RG 76-C. Department of Employment and Immigration fonds. Library and Archives Canada Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

(b) Passport Application. Form for Native Citizen. United States of America. July 10, 1924. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 2601; Volume #: Roll 2601 – Certificates: 457850-458349, 14 Jul 1924-14 Jul 1924. Source Information: Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. Original data: Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Marriage Certificate. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, D.C.; Marriage Reports in State Department Decimal Files, 1910-1949; Record Group: 59, General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002; Series ARC ID: 2555709; Series MLR Number: A1, Entry 3001; Series Box Number: 475; File Number: 133/476. Source Information: Ancestry.com. U.S., Consular Reports of Marriages, 1910-1949 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc.

R.M.S. Empress of Asia passenger List, Yokohama – Victoria B.C. Ancestry.com. Canadian Passenger Lists, 1865-1935 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists, 1865–1935. Microfilm Publications T-479 to T-520, T-4689 to T-4874, T-14700 to T-14939, C-4511 to C-4542. Library and Archives Canada, n.d. RG 76-C. Department of Employment and Immigration fonds. Library and Archives Canada Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Lisa Lethin. “My Grandfather was the Partner of Joe Babcock”. (In Dutch) http://www.mahjongmuseum.nl/mijn-groot-vader-was-de-zakenpartner-van-joe-babcock/

(a) Department Passport Application – Native. March 2, 1917. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications for Travel to China, 1906-1925; Box #: 4433; Volume #: Volume 20: Emergency Passport Applications: China. Source Information: Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007.

(b) Department Passport Application – Native. March 6, 1917. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications for Travel to China, 1906-1925; Box #: 4433; Volume #: Volume 20: Emergency Passport Applications: China. Source Information: Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. Original data: Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Department Passport Application – Native. April 22, 1918. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 757; Volume #: Roll 0757 – Certificates: 77750-77999, 26 Apr 1919-28 Apr 1919. Source Information: Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007.[Note] This application gives an incorrect departure date from San Francisco. It should be January 17, 1917.

See footnote 20.

See footnote 22.

See footnote 21.

Application for Registration – Native Citizen. February 24, 1919. Roll #: 32734_620305173_0270. Source Information:Ancestry.com. U.S., Consular Registration Applications, 1916-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Original data: Department of State, Division of Passport Control Consular Registration Applications.

S.S. Equador Passenger list. Ancestry.com. California, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008. Original data: Selected Passenger and Crew Lists and Manifests. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

See footnote 7.

Application for Registration – Native Citizen. September 18, 1920. Roll #: 32734_620303987_0274. Source Information:Ancestry.com. U.S., Consular Registration Applications, 1916-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Original data: Department of State, Division of Passport Control Consular Registration Applications.

Department Passport Application – Native. September 23, 1921. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 1770; Volume #: Roll 1770 – Certificates: 95250-95625, 03 Nov 1921-04 Nov 1921. Source Information: Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. Original data: Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

See footnote 30.

(a) S.S. President Lincoln, Passenger List Ancestry.com. California, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008. Original data: Selected Passenger and Crew Lists and Manifests. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

(b) The ‘SS President Lincoln’ used by Babcock to traverse the Pacific, was originally called the ‘Hoosier State’. The ‘Hoosier State’ was originally built for the United States Shipping Board in 1922 and had its name changed in that year to ‘SS President Lincoln’. It belonged to a fleet of ships managed by the Pacific Mail SS Company that was a subsidiary of the Grace Line, until 1925 when the PMSS Co., was purchased by the Dollar Line.

Joseph P. Babcock. Form for Native Citizen. United States of America. July 10, 1924. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 2601; Volume #: Roll 2601 – Certificates: 457850-458349, 14 Jul 1924-14 Jul 1924. Source Information: Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. Original data: Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

See footnote 7.

(a) See footnote 33.

(b) Norma N. Babcock. Passport Application. Form for Native Citizen. United States of America. July 10, 1924. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 2601; Volume #: Roll 2601 – Certificates: 457850-458349, 14 Jul 1924-14 Jul 1924. Source Information:Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. Original data: Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Anton Nathaniel Lethin (Pronounced Leh-THEEN) (1887-1966) arrived in China July 191536 and joined the Shanghai branch of the International Correspondence Schools37 headed by Albert R. Hager who was the General Manager/Agent for the International Correspondence Schools based in China, Japan, Korea and the Phillipines38. He volunteered to serve in China during the first World War, joining the Voluntary Civil Service from 1915-1919. His residential address was at 680 Avenue Joffre and his office address was 73 Szechuen Road, Shanghai, (the office address of A. R. Hager and therefore of the Shanghai branch of the International Correspondence Schools)39.

In November 1916 he returned to the United States to marry Helen Van Housen whom he had met during a previous visit. They departed San Francisco on January 17, 191740 setting sail for Shanghai on the Siberia Maru41 for Shanghai, China, arriving on February 13, 191742.

By 1920 he was manager of the China Agency of the International Correspondence Schools in Shanghai, where he and his wife were residing since returning from the United States three years earlier. Their United States address was given as 202 Wellington Avenue, Elgin, Illinois43,44. While Albert Hager was visiting the United States on business, ~ 22 September 1922 – 21 February 1923, Lethin managed the Business Equipment Corporation, the International Correspondence School (Shanghai) and was the permanent manager of the Mah-Jongg Company of China45.

Lunt. C. The China Who’s Who 1925 (foreign): a biographical dictionary. Shanghai, 1925.

The Educational Directory and Yearbook of China, Shanghai, 1920, P.52.

See Footnote 1.

See Footnote 36.

See Footnotes 21 & 22.

See Footnote 20.

See Footnote 22.

The Educational Directory and Yearbook of China, Shanghai, 1920, P.83.

See Footnote 36.

See Footnote 5.

The story of how the Chinese game of mo ziang/má jiàng (Sparrows) became a popular Westernised version called Mah-Jongg – initially via the Mah-Jongg Company of China – really begins with the experiences of Joseph Park Babcock in Shanghai, then Tianjin and Peking. After a year and a half in Peking he met and eventually married Norma Noble who had arrived in China in November 1915. Following their subsequent trip to the United States they returned to China, residing in Harbin, then Suzhou and Jinan. It was from these centres that they encountered different variations of the game. He and his wife Norma Babcock also revisited these cities in the course of their travels and used their residences as centers for their travels into the interior of China.

There are two sources of original testimony by the Babcocks. The first is a letter by Joseph Babcock accompanying an advertisement in the The Saturday Evening Post, December 15, 1923. The second is an article by Norma Babcock in The Catalina Islander newspaper April 16, 1924. The accounts given in these two testimonies are supported by the biographical and geographical information taken from the sources listed in the references above as well as original testimony given by Anton Lethin in his important 1923 letter to his elder sister, Agnes.

Joseph Babcock began his account by stating46:

“During the past ten years I have spent a great part of my time travelling in the interior of China, where I was dependent almost entirely on the Chinese for my recreation. Speaking the Chinese language, I became interested in a game played by the Chinese, with attractive tiles of bamboo and ivory, … I was immensely impressed, not only by the entertainment, but by the cultural features of this game.”

Norma Babcock also recalled similar circumstances:47

“… in those early days he went on frequent journeys into the interior. In this way, and because of his knowledge of their language, he was soon initiated into the mysteries of the Chinese tile game. …

When you add … an insatiable curiosity, it is easy to see how he became interested in these Chinese games. In Peking [Beijing], Tientsin [Tianjin], Shanghai, and many other cities of North China and Manchuria, he saw and studied these various games.”

If Babcock was speaking Mandarin then that would have enabled him to communicate with Chinese officials when performing his job. However, this may have posed some problem in the South East of China where Mandarin was less widely spoken.

From Shanghai he was able to visit Suzhou and Nanjing to the West and Ningbo and Hangzhou to the South. Jinan to the South East and other cities in North Western China would have been accessible to him from Tianjin. This would have been particularly significant after he took up his first important residence in Peking [Beijing], where he arrived June 25, 1914 – after the five months spent in Shanghai and just under six months spent in Tianjin. From Peking he would have had a more economical striking point to the interior of North China and hence to the north China variants of má jiàng, where they existed.

By October 1916 he had married Norma Noble in Kobe Japan and travelled to Canada and then to the United States to introduce her to his parents in Lafayette, Indiana. On their train journey to San Francisco from where they would sail to China, the Babcocks met Anton Lethin and Helen van Housen-Lethin – also travelling to San Francisco and then to China. According to Anton Lethin48;

“Helen and I met Mr and Mrs Babcock on our wedding trip when we boarded the train at Ashland, Oregon. Since that time we have been very friendly with them.”

On January 17th 1917 the two couples sailed to Shanghai aboard the Siberia Maru.

Upon their arrival on February 13, 1917, the Lethins took up residence in Shanghai for Anton Lethin’s post in the International Correspondence Schools’ Shanghai division headed by Albert R. Hager. The Babcocks on the other hand, immediately travelled North to Harbin, Manchuria, where they arrived six days later on February 19, 1917. Joseph and Norma Babcock spent approximately seven months residing in Harbin, with opportunities to travel to the far North West and North East of China and also into Korea.

After their residence in Harbin they travelled south to Suzhou, arriving in September 1917. According to Norma Babcock49:

“Six or seven years ago [since she was writing in 1924 then “seven years ago” would be accurate to allow the date of 1917] we were living in the tiny foreign colony of Soochow [Suzhou]. There were only twelve people in the community where we lived, but we were only a short distance from the high wall of the Chinese city, which held a population of half a million Chinese. Situated as we were, in close contact with interesting Chinese people, we had few amusements in our small community of Americans and Europeans. My husband became an expert and close student of the Chinese game as it was played in Soochow [Suzhou].”

Now that they were stationed in Suzhou, the Babcocks must have re-established their friendship with Anton and Helen Lethin who were living in Shanghai. Their friendship with the Lethin’s would also allow them to become acquainted with Albert Hager and his wife Emily Hager through the Lethins’ friendship with the Hagers, as evidenced from pictures of the Lethins visiting the Hagers socially(see Figures 3 and 4 below).

Albert Hager also appeared to have come across the game. R. F. Foster (1924) reports an account by Hager that appears, from Foster’s wording, to be a direct communication from Hager about his experiences in China. It seems that Hager had also observed the game while serving as a volunteer policeman in China during the 1914-1919 world war.

By July 1919 Hager may have met Joseph Babcock via his friendship with Anton Lethin who worked for and was friends with Hager (note the different spelling of Hager’s surname). As Foster reports50:

“We are told that is was in July, 1919, that Mr. Babcock tried to interest Mr. Hagar in the game and the possibilities of exploiting it in the United States. Up to that time Mr. Hagar tells us, he had considered it too intricate and baffling ever to be popular with foreigners, …

Being ‘close’ neighbours, the Babcock’s and Lethin’s met frequently for social gatherings, as Lisa Lethin describes51:

“The Babcocks lived in Soochow [Suzhou] and the Lethins in Shanghai, and sometimes the Lethins would visit them in Soochow and sometimes the Babcocks went to Shanghai. … In 1920, my grandparents had a little daughter, Onnette. … The following story she heard from her parents (Anton and Helen Lethin). “Joe had been on a houseboat on the Yangtze River. (Dad wasn’t with him at the time.) The wind died down, and they were stranded on the river. So the Chinese got out this game to play. Joe was definitely a linguist; he did know Chinese. He was able to deal with the game and the rules and everything.”

By this time Joseph Babcock and perhaps Norma Babcock would have been well acquainted with the many local variations of mo ziang/má jiàng (Sparrows) from their extensive travels throughout China, and so the fundamental rules and game play would have been familiar to them. Further, from that perspective, the “unknown and strange game” was likely a strange and unknown variation or perhaps another tile game such as the domino game of wā huā (which also used the Flowers and Seasons tiles found in má jiàng).

Anton Lethin(1923) comments on their activities when they visited the Babcocks52:

“In the fall of 1919 we were visiting the Babcocks in Soochow [Suzhou], a town about thirty miles from Shanghai. Mr Babcock works for the Standard Oil Co. and has to associate with the Chinese a great deal and learned to play Mah-Jongg with them. He suggested we play the game when we were looking for something to do that time in Soochow, but we found it somewhat confusing as it was necessary for us to first learn to read the Chinese numerals and the characters denoting the four winds. After we returned to Shanghai, to help us out, he had a special set made up for us with the Arabic numerals and the E, W, N and S, which enabled us to play the game without knowing the Chinese.”

This resonates with Norma Babcock’s (1924) account of her husband’s successful attempt to overcome the Lethin’s problem53:

“… he tried to get the English numerals placed at the corner of the tiles, as you see them today [1924]. While there were several small shops where sets of these tile games were made, not a single workman cared to attempt the making of strange English numbers and letters, which meant nothing at all to them …

… My husband finally persuaded one of them to try it. … After several attempts he eventually succeeded in marking the first set of tiles with the properly placed foreign letters and numerals.

This very man, Wong Liang Sung, is today the acknowledged plutocrat of the mah jongg industry among the Chinese… .”

It seems that Albert Hager may have become aware of the ease of play with this new set via socialising with the Lethins and watching them play. Thus, according to Anton Lethin54:

“Hager made a trip to Soochow [Suzhou] later on and became interested, and after the Hagers [Mr and Mrs Hager] and ourselves had begun teaching friends, we saw the commercial possibilities.”

R. F. Foster’s (1924) report also describes this meeting in Suzhou55:

… Upon Mr. Babcock’s representation that the difficulties foreigners had with the game were largely due to the want of English translations of the terminology, and the whole thing could be simplified…. . And by always putting English numerals on the tiles, Mr. Hagar began to see the light.”

This explanation for overcoming the difficulties foreigners had with the game is reinforced by Babcock’s own account56:

“It seemed to me that, if properly introduced, it would appeal tremendously to Americans and Europeans. …

… I saw that it would be necessary, therefore, for me to write rules of my own and devise my own terminology …”

and

“…inventing what I call “index playing symbols”. These are the English letters and numbers in the corners of the tiles … .”

From this series of accounts, it seems that the Hagers were introduced to the Chinese game in July 1919 when they had visited the Babcocks in Suzhou (via their friendship with the Lethins), but had decided the game was too difficult for foreigners. However, after Joseph Babcock had had a set made for the Lethin’s with the Arabic numerals and English letters included on the tiles, the Hagers may have witnessed the Lethin’s ease of play, undoubtedly during their socialising at the Columbian Country Club in the outer suburbs of Shanghai. According to Lisa Lethin (in private correspondence), the Lethins lived at the club probably from 1918-1920 and Anton Lethin was the Club Secretary.

This would provide motivation for Albert Hager to make a further trip to Soochow [Suzhou] in late 1919, and it was then that Babcock had explained his idea of how to overcome the difficulties experienced by foreigners.

It might have been at this point that Hager, Babcock and Lethin decided to buy as many tile sets as they could find in the Chinese shops and “left there to put Western numbers and letters [on the sets]”57 and to distribute them to their friends in Shanghai.

Thus Albert Hager and his wife, together with Anton Lethin and his wife explained and taught the game to friends in Shanghai, again most likely at the Columbian Country Club where the Lethins were staying, and as a consequence discovered there was commercial potential from the game.

According to Norma Babcock(1924) her husband had also coined a name for his version of the game58:

“The Chinese tile game, named mah jongg by my husband for play by his friends…”

Joseph Babcock (1923) also claims to have created the name for his game59:

“To designate the game as I evolved it, with these English indices and with the codified and standardized Babcock rules, I applied the word “Mah-Jongg,” pronounced “Mah-ZHONG”, trade marked it in the U.S. Patent Office and applied it also to my book of rules which I had copyrighted.”

As we shall see below, this rendition of the name of his game appears to be the version trademarked by Hager.

On 28th March 1920 the Babcocks sailed for San Francisco where they arrived on April 22, 1920 and sometime later took up residence at a villa on the island of Catalina60:

“It was really here at Catalina that the idea of introducing mah jongg to America originated. It was at the Island Villa, the summer of 1920, that we, on top of the funny little Chinese traveling box, first set up a wall of Chinese bamboo tiles on good old American soil, and proceeded to have what we thought would be a quiet little game. But soon all the Island’s summer visitors were clustered about us, it seemed, and we were more an object of curiosity than a three-hundred pound tuna.

A publicity correspondent made the most of a story about the new game in a Los Angeles newspaper and the thing was done. Before we reached San Francisco to re-sail for the Orient it seemed as though all of California and his wife had commissioned us to bring them a mah jongg set when we came again, or at least to send them one.

Well, we sent them … seventeen ship loads of them!”

They departed San Francisco on July 29, 1920 and arrived in Tsinan [Jinan] on August 19, 1920, where Joseph Babcock was on business on behalf of the Standard Oil Company61….

Babcock, Joseph P. ‘MAH-JONGG. Its Authentic Source’. In: The Saturday Evening Post, p. 127. Dec. 15, 1923.

Babcock, Norma N. ‘MAH JONGG Started in Popularity at Catalina’. In: The Catalina Islander, p2 & p10. Apr. 16, 1924.

See Footnote 5.

See footnote 47.

Foster. R. F. ‘Foster on Mah Jong Mah Cheuk Ma Chang Pung Chow’. Dodd, Mead and Company. 1924.

See footnote 20.

See footnote 5.

See footnote 47.

See Footnote 5.

See footnote 50.

See Footnote 46.

See Footnote 20.

See Footnote 47.

See Footnote 46.

See Footnote 47.

Application for registration – Native Citizen. September 18, 1920. Roll #: 32734_620303987_0274

Source Information:Ancestry.com. U.S., Consular Registration Applications, 1916-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

Original data: Department of State, Division of Passport Control Consular Registration Applications.

… And so, a month later in September 1920 according to the printing history of his small hard cover book of rules, Joseph Babcock had printed his first edition booklet of rules titled ‘Rules for Mah-Jongg”. (Note the absence of Babcock’s name in the title.)

Albert Hager, on the other hand, began filing trademark and patent applications. The first was for a trademark, filed October 24, 192162:

“US Patent Office, Official Gazette, Feb. 14, 1922 [Trade-mark] Ser. No. 154,510

Albert R. Hager, Salt Lake City, Utah. Filed Oct. 24, 1921.

Mah-Jongg

麻

雀

The Japanese characters appearing on the drawing mean, in English, “Sparrows”. Particular description of goods. 輸 Game played with pieces somewhat similar to dominoes.

Claims use since on or about the 26th day of October, 1920.”

Anton Lethin [Lethin also mentions that Hager had been in the United States for the past six months, that is, since September 1922] gives a valuable insight into the formation of the Mah-Jongg Company of China and the way the Company’s orders from its subsidiary the Mah-Jongg Co. of America were fulfilled 63:

“We organized the Mah-Jongg company about a year ago forming a partnership consisting of Mr Hager, Joe Babcock, the chap that wrote the “Little Red Book of Rules” and myself. I was able to take only a small interest in the company when it was started, but before Mr Hager went to the States [Lethin also mentions that Hager had been in the United States for the past six months, that is, since September 1922] I secured his and Babcocks agreement permitting me to acquire interest equal to theirs if I would subscribe additional capital within six months from August 11th. … It looked for several months back as though it might not be desirable for me to increase my interests … but things were straightened out just in time for me to get aboard … .”

… Most of the sets are made from shin-bone — only the shinbones in the forelegs of cattle being used. Most of this material comes from the slaughter houses in Chicago. Some bone is obtained in China, but as they dont know the secret process for bleaching it properly, the native bone is used only in cheaper sets.

This shin bone is cut up into pieces that go into the MJ tiles, sawn, filed down to form the dovetail and polish all by hand. The bamboo that forms the back is also entirely cut out by hand. This work is entirely a household industry, one family of workers being able to turn out perhaps only one set in a day. The blanks are then purchased by the manufacturers, who carve the faces, and the shops in which this carving is done, usually average not over a hundred sets per month. So when it comes to filling orders from America for hundreds of sets, it is quite a job to purchase them.”

From these extensive excerpts we know that “a year ago” would therefore approximate to early 1922 since Anton Lethin’s letter was dated February 18, 1923. Thus the “Mah-Jongg Company” of China was formed very early in 1922. But note the spelling for the name of the Company. Hager, as we shall see below, spelled it “Mah-Jong” whereas when referring to the game and the Company Lethin used the name “Mah-Jongg”. Babcock also used the latter term for the designation of the game as well as for the Company.

Further, it is clear that the China Company fulfilled its orders by purchasing sets from individual manufacturers that were in reality small family run enterprises at the end of a very long chain, consisting of other small enterprises that were involved in the purchase of the bone and the bamboo and its preparation and production into blank tiles. This is supported by a brief account given by Babcock to The Los Angeles Times, October 25, 1923:

“”Most of them are made in Shanghai” explained Mr. Babcock. The carving industry is a household art, so the sets as well as the boxes are made here and there. I don’t know, but thousands must be employed making them”.

The time of the formation of the China Company is also reinforced by Hager’s next Patent application for a ‘Cabinet for Holding Games’, filed May 25, 192264:

“Patented Dec. 11, 1923. 1,477,056

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE.

ALBERT R. HAGER, OF SHANGHAI, CHINA, ASSIGNOR TO THE MAH-JONG COMPANY OF CHINA, OF SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA, A COPARTNERSHIP CONSISTING OF JOSEPH PARK BABCOCK, ANTON N. LETHIN, AND ALBERT R. HAGER.

CABINET FOR HOLDING GAMES.

Application filed May 25, 1922. Serial No. 563,701.”

The filing date of May 25, 1922, is the earliest mention of the Mah-Jong Company of San Francisco (using Hager’s spelling ‘Mah-Jong’). However, by at least July 1922 the Mah-Jongg Company of San Francisco had become the Mah-Jongg Sales Company of America (using Lethin and Babcock’s spelling ‘Mah-Jongg’), 112 Market St., San Francisco, as found on the machine stamp on the back cover of ‘Babcock’s Rules for Mah-Jongg’ 1922 edition booklet65. Anton Lethin names the company’s founders66:

“Business began to boom last Fall [September – November], orders galore being received from the Mah-Jongg Sales Co. of America, a company formed by Hager, Babcock and Mr Hammond in San Francisco.”

Therefore some time before May 25, 1922, this company must have been formed by the copartners of Joseph P. Babcock, Albert R. Hager and the lumber merchant, W. A. Hammond Co., of 112 Market St. San Francisco67. Also, it was Hammond who began the;

“… importation of sets in large quantities. Mr. Hammond informs me that up to September 1, 1922, he imported $50,000 worth of sets, out of a total of $56,000 reported by the Chamber of Commerce as having been shipped from Shanghai, up to that time.”68

But note that in Hager’s patent application he does not mention Hammond.

However, importation of sets was to greatly increase. Thus, nearly a year later, on October 9, 1923, the Babcocks arrived at San Fransisco on the S.S. President Lincoln and, according to the Los Angeles times, October 25, 1923;

“Mr. Babcock arrived on the steamship President Lincoln. In the hold were 170 tons of ivory and bamboo in mah jongg sets. When the President Taft arrives in a few days it will bring three times that pound weight of mah jongg dominoes and toothpicks. Mr Tees estimated that some 300,000 sets already have been sold in this country.”

The 300,000 sets probably incorporated those sold by W. A. Hammond as well. But by the end of 1923 at least an extra 680 tons of sets had been imported into the United States.

Norma Babcock may have alluded to this and future importations with her 1924 remark “Well, we sent them, … seventeen ship loads of them!”69

But with the sudden increase in sales and finances, the American Company soon began to experience problems70:

“However, the financial end of the American business soon assumed such gigantic proportions that Mr Hager considered it advisable to make a trip to the States. Fortunately he did so, as the American company became over enthusiastic and Mr Hager has had quite a job straightening things out. They are now well out of the woods…. From all reports I have had, Mah-Jongg is certainly taking the country by storm. The China company controls the trademarked name “MAH-JONGG” as well as the copyrighted rules.“

The hard work and business acumen of Albert Hager therefore saved the American arm of the Mah-Jongg Company of China. Hager’s next application was for a Patent for a ‘Game-scoring Device’, filed September 25, 192271:

“Patented Apr. 3, 1923. 1,450,852

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE.

ALBERT R. HAGER, OF MANILA, PHILIPPINE ISLANDS.

GAME-SCORING DEVICE.

Application filed September 25, 1922. Serial No. 590,430.”

These applications were probably alluded to by Anton Lethin as “advantages”72:

“Mr Hager has been endeavouring to secure additional advantages, but just how successful he has been I will not know until he arrives from the States, three days from now.“

This would place Hager returning to Shanghai February 21, 1923.

Perhaps one of his last acts before returning to China was the publishing of a new book of rules. As Anton Lethin states73:

“While Mr Hager was in the U.S. he had a new rule book printed including about a hundred pages and around 50 illustrations.”

This book was most likely the revised and enlarged, second edition hardcover version of Babcock’s booklet ‘Rules for MAH-JONGG The Red Book of Rules’. Titled 麻雀 Babcock’s Rules for MAH-JONGG The Fascinating Chinese Game’, it was printed in the United States and published February 1923.

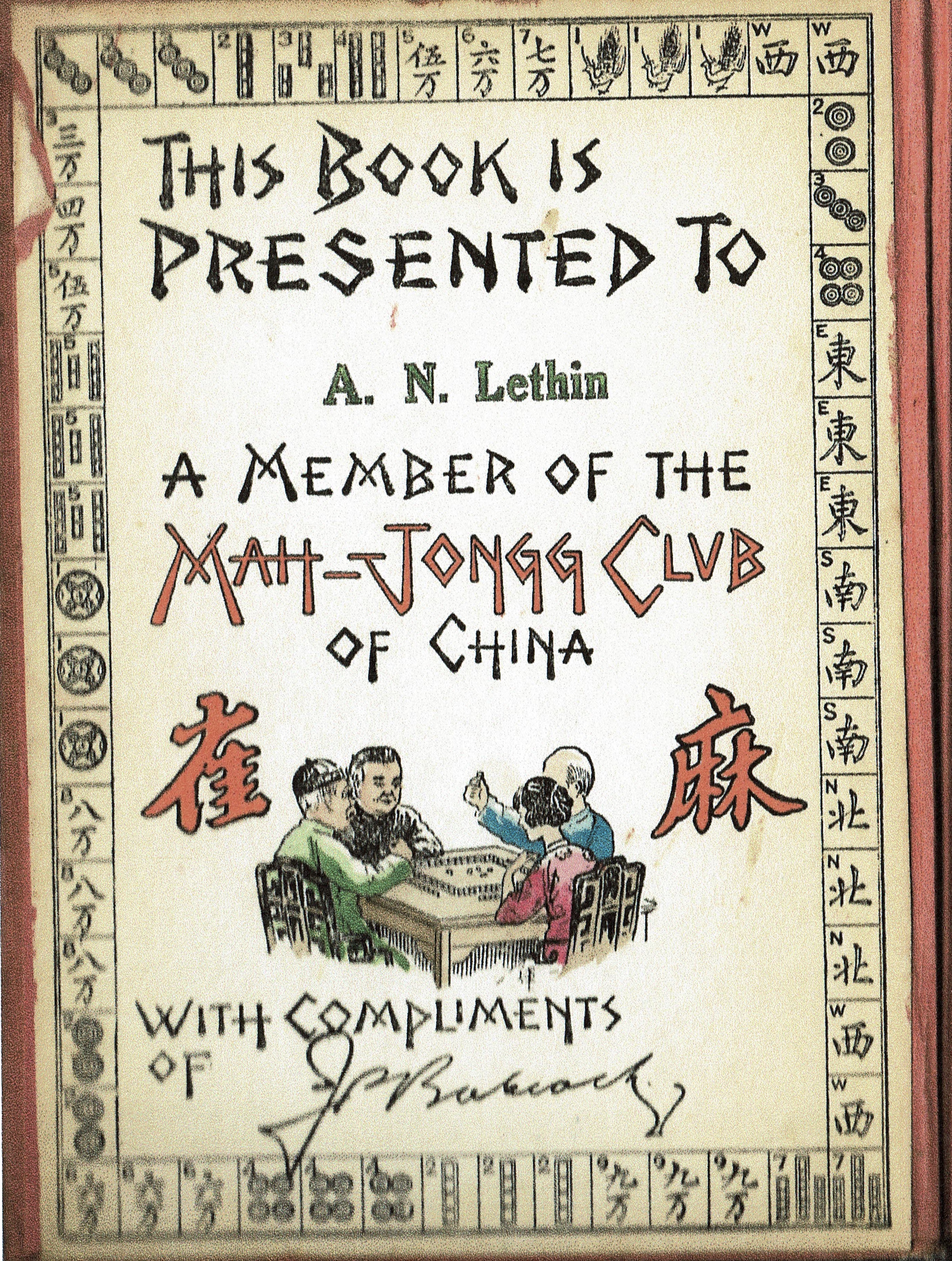

Anton Lethin had a copy of this edition of the rule book as a presentation copy for being a member of the MAH-JONGG CLUB of China. It appears to have been presented by his friend J. P. Babcock as Babcock’s signature attests at the bottom of a very fine presentation page pasted into the book (Figure 10).

Next, Joseph Babcock applied for a Patent for a ‘Game’ on November 4, 1922. Serial No. 599,107. However, there is no patent for this application Serial Number. It was most likely refused due to the intervention by Stewart Culin when he;

“informed the patent office that the set in question had pieces “identical” to the set he had purchased in 1909″74

The outcome of this intervention was no doubt the Patent Officers view that the patent lacked originality.

By 1922 the Babcocks were still residing in Tsinan [Jinan].

On February 23, 1923 Joseph Babcock filed for a trademark75:

“(US Patent Office, Official Gazette, July 22, 1924)

[Trade-mark] Ser. No. 176,488 (CLASS 22. GAMES, TOYS AND SPORTING GOODS.)

The Mah-Jongg Sales Company of America, San Francisco, Calif. Filed Feb. 23, 1923.

MAH-JONGG

Particular description of goods.—Games played with pieces somewhat similar to dominoes.

Claims use since on or about Oct. 26, 1920.”

As was mentioned earlier, there is a discrepancy between Hager’s and Babcock’s logos for the game. Hager’s term is “Mah-Jongg” or “Mah-Jong”whereas Babcock’s is “MAH-JONGG” and both claim a “use since on or about October 26, 1920”. This is immediately following the September publication of the first edition of Babcock’s “Rules for Mah-Jongg”, which sports Hager’s trademarked logo.

More importantly, in his letter in The Saturday Evening Post, December 15, 1923, Babcock said that;

“To designate the game as I evolved it, … I applied the word “Mah-Jongg,” … , trade marked it in the U.S. Patent office and applied it to my book of rules which I had copyrighted.”

However, that logo was trade-marked by Albert R. Hager, not Babcock. It may have been at the behest of Joseph Babcock however, since they were both partners in the Mah Jongg Company of China.

At the same time as these filing activities and under the guidance of Anton Lethin, the Mah-Jongg Company of China had been ordering and purchasing tile sets for export. As a consequence, about nine months later on September 19, 1923, the Babcocks had set sail aboard the S.S. President Lincoln laden with 170 tons of “bamboo and ivory” Mah-Jongg sets.76 They arrived at San Francisco on October 9, 1923 where Joseph Babcock gave his occupation as “marketer”.

Following his arrival in the United States, Joseph Babcock filed another patent application on December 19, 192377. Since his first application was refused, after “improved” specifications this was considered a continuation of the patent application he had filed just under a year earlier:

“Patented Sept. 22, 1925 1,554,834

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE

JOSEPH PARK BABCOCK, OF TSINAN, CHINA, ASSIGNOR TO MAH-JONGG COMPANY OF CHINA, OF SHANGHAI, A CORPORATION OF ALASKA.

Game.

Continuation of application Serial No. 599,107, filed Nov. 4, 1922. This application filed December 19, 1923. Serial No. 681,584.

To all whom it may concern:

Be it known that I, Joseph Park Babcock, a citizen of the United States, residing at Tsinan, China, whose post-office address is Friendship, New York, have invented an improvement in games, of which the following is a specification.

This invention relates to a game and this application is a continuation of my co-pending application Serial No. 599,107 filed November 4, 1922.

In the drawing I have illustrated in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 a set of game pieces or tiles with which the game may be played. …”

And so, following a two-year examination, the U.S. Patent Office granted Joseph Babcock a patent on September 22, 1925. Unfortunately, by 1925 the Mah-Jongg boom had collapsed.

He also applied for a design, filed December 14, 192378:

“US Patent Office, Official Gazette, Oct. 21, 1924.

[Design] No. 65,794. SET OF DOMINOES.

Joseph Park Babcock, of Tsinan, China, assignor to Mah Jongg Company of China, Shanghai, China, a Corporation of Alaska. Filed Dec. 14, 1923. Serial No. 8,039. Term of patent 3 ½ years.“

Following his patent and trademark filing activities, both he and Norma Babcock were booked for a return trip to China from Seattle on the S.S. President Grant, July 31, 1924. It is not clear whether they left for China however. By 1925 he was a student at Yale studying Law79.

rec.games.mahjong

‘MJ US Trade-marks of the 1920’s’

Thierry Depaulis Post 23/6/04;

https://groups.google.com/forum/#!searchin/rec.games.mahjong/MJ$20US$20Trade-marks$20of$20the$201920$27s/rec.games.mahjong/Vh2W35ACH2k/qvCY4OU3u4kJ

See Footnote 5.

http://pdfpiw.uspto.gov/.piw?Docid=01477056&homeurl=http%3A%2F%2Fpatft.uspto.gov%2Fnetacgi%2Fnph-Parser%3FSect1%3DPTO2%2526Sect2%3DHITOFF%2526p%3D1%2526u%3D%25252Fnetahtml%25252FPTO%25252Fsearch-bool.html%2526r%3D1%2526f%3DG%2526l%3D50%2526co1%3DAND%2526d%3DPALL%2526s1%3D1477056.PN.%2526OS%3DPN%2F1477056%2526RS%3DPN%2F1477056&PageNum=&Rtype=&SectionNum=&idkey=NONE&Input=View+first+page

rec.games.mahjong.

‘Babcock’

Tom Sloper post 1/3/03

W. A. Hammond Co, hand-stamp on the back cover of Babcock’s 12 page ‘Rules for Mah-Jongg’.

https://groups.google.com/forum/#!searchin/rec.games.mahjong/W.$20A.$20hammond/rec.games.mahjong/jIBG3bCayRQ/6BPeOQYlkCMJ

See Footnote 5.

Ibid.

See Footnote 50.

See footnote 47.

See Footnote 5.

http://pdfpiw.uspto.gov/.piw?Docid=01450852&homeurl=http%3A%2F%2Fpatft.uspto.gov%2Fnetacgi%2Fnph-Parser%3FSect1%3DPTO2%2526Sect2%3DHITOFF%2526p%3D1%2526u%3D%25252Fnetahtml%25252FPTO%25252Fsearch-bool.html%2526r%3D1%2526f%3DG%2526l%3D50%2526co1%3DAND%2526d%3DPALL%2526s1%3D1450852.PN.%2526OS%3DPN%2F1450852%2526RS%3DPN%2F1450852&PageNum=&Rtype=&SectionNum=&idkey=NONE&Input=View+first+page

See Footnote 5.

ibid.

Culin to C. C. Henry, U.S. Patent Office, May 19, 1924, folder 068, Series 1.4, Culin Archival Collection. Brooklyn Museum, NY.

rec.games.mahjong

‘Babcock’s Mah Jongg Patent.’

Thierry depaulis post. 21/6/04

https://groups.google.com/forum/#!searchin/rec.games.mahjong/BABCOCK$20PATENT/rec.games.mahjong/omhEMVeGvnw/4LhUJzf4IYwJ

(a) Footnote 25. “Mah Jongg King Arrives in City: Game originator Frightened, but Not Ashamed” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 25, 1223, section 2, p.10 in: Greenfield, Mary C. “The Game of One Hundred Intelligences: Mahjong, Materials, and the Marketing of the Asian Exotic in the 1920s.” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 79, No. 3 (August 2010). pp. 329-359.

(b) With reference to the ‘SS President Lincoln’; this ship should not be confused with its namesake that was sunk by a torpedo in May, 1918. See Footnote 32 for clarification.

http://pdfpiw.uspto.gov/.piw?Docid=01554834&homeurl=http%3A%2F%2Fpatft.uspto.gov%2Fnetacgi%2Fnph-Parser%3FSect1%3DPTO2%2526Sect2%3DHITOFF%2526p%3D1%2526u%3D%25252Fnetahtml%25252FPTO%25252Fsearch-bool.html%2526r%3D1%2526f%3DG%2526l%3D50%2526co1%3DAND%2526d%3DPALL%2526s1%3D1554834.PN.%2526OS%3DPN%2F1554834%2526RS%3DPN%2F1554834&PageNum=&Rtype=&SectionNum=&idkey=NONE&Input=View+first+page

rec.games.mahjong

‘MJ US Trade-marks of the 1920’s’

Thierry Depaulis post. 21/6/04

https://groups.google.com/forum/#!searchin/rec.games.mahjong/MJ$20US$20Trade-marks$20of$20the$201920$27s/rec.games.mahjong/Vh2W35ACH2k/qvCY4OU3u4kJ

United States Census, June 1, 1925. Friendship, Allegany County, New York, United States. Joseph Babcock. ‘Student College’.

Testimony of Christopher Babcock Berg; Joseph Babcock studying Law at Yale.(Private correspondence.)